The European Beaver (Caster Fiber) was native in Britain although they have been extinct for four centuries now. Beavers are the world’s second largest rodents, and our variety is larger than their American cousin. They are easily recognisable by their large flat tail, stocky build and deep brown fur. Being herbivores, they use their sharp teeth to down trees in order to chomp at their favourite meal, bark. They use the stripped trunks to build their homes or ‘lodges’, which form leaky dams to small streams, in the process forming deep pools and wetlands behind them.

Doing what they do best as landscape engineers, beavers have come into conflict with us humans. In the past we liked them for their fur, and so hunted them to extinction. Today we don’t figure them to be part of our landscape, and so discriminate against their habitation with our own land use plans.

It is not just the beavers that are having troubles with the environment they live in; we are also currently facing some major challenges that need to be overcome. We are releasing huge amounts of carbon in exchange for our hunger for energy, having the affect of turning up the thermostat. This is having the undesirable knock on effect of our climate changing at an unprecedented pace, a pace that the natural world is having difficulty keeping up with. For us in the UK, this is leading to more unpredictable rainfall patterns.

There are lots of us, and we use far more than our fair share of water to keep us going. Here in South East England we seem to be constantly water stressed; it either rains to fast for us to do anything with, or, not enough of it falls to satisfy our demands. Our current approach to water management relies on the basis of quickly evacuating it by guiding it swiftly off our land in highly engineered rivers and culverts and in to the sea. The rivers and streams swell and dry uncontrollably, making them hostile places for our wildlife to live. The fast flow of water erodes our precious land, taking away the goodness and wealth of nutrients held within the soil. This puts a lot of pressure on the pinch points in the river systems, causing them to overflow with ease, flooding homes, ruining crops and drowning livestock. This fast evacuation also doesn’t allow much of that water to percolate down to replenish our aquifers, the land sponges that provide us with our potable water. It doesn’t take long for our reserves to run out, putting restrictions on our activities, and putting us at risk.

Of course, the UK Environment Agency does a good job of spending large amounts of taxpayers money installing and maintaining defences against flooding. It could be argued that is a fairly futile task, fighting the symptoms of the problem, rather than the causes of them. What we really need is a cost effect way of combating the causes to our problems rather than dealing with the symptoms at great cost. This is where the potential of beavers could be realised.

Beavers slow down water systems, slowing the lag time of storm water reaching the system pinch points. This reduces peak load stress and the potential for damage caused by flooding. Slow water systems allow for detoxifying microorganisms to get to work at man made pollutants such as pesticides, making for a less costly purification process of the water abstracted downstream for consumption. Slower water can’t erode the land so easily and the silt that drops out can be used to fertilise the land. The water also has the chance to percolate down and recharge our aquifers. Slower systems have more water in them, meaning the land doesn’t become parched so quickly when the rain fails to fall.

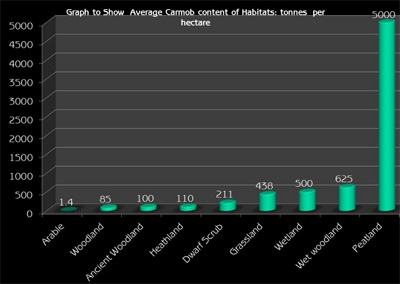

The wetlands that Beavers create have huge positive implications for biodiversity. The plant life held within the ponds, bogs and water meadows created up stream from the dams are hugely diverse habitats and masses of biodiversity are held within them. This helps to tackle the whole raft of challenges we face as a result of biodiversity loss. The marshy bogs that are created will become peatlands as dead vegetation accumulates underwater. Peatlands are hugely effective at carbon sequestration, sinking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and locking it away on land.

The Wildwood Trust reintroduced beavers to the last remaining fen in Kent. Within 10 years this delicate habitat has been transformed onto a diverse and vibrant place, at negligible cost. It can be seen that re-introducing beavers can be catalyst for a whole range of positive effects on the environment, from managing flood risk and providing habitats to create massively diverse ecosystems, to even helping fight the battle against greenhouse gases.

We need to accept a certain loss of land as a trade-off to this, but this relatively small cost must be far outweighed by the advantages it brings. It can only be a positive thing to learn to co-exist with the beaver once again, and secure our future against the challenges change will bring. Our long-term prosperity lies taking measures to naturally enhance the environment, not the engineering of the landscape to suit our immediate needs.

By Russell Stevens

Conker Conservation Ltd.

Image Credits: Wildwood

Posted August 2013