It is estimated that 54% of the world’s population now lives in urban areas and that proportion is expected to increase to 66% by 2050. That fact, and the predicted global population growth could mean another 2.5 billion people to the number of urban dwellers within the next 32 years, with 90% of that increase concentrated in Asia and Africa.

This makes Sustainable Development Goal 11 – Sustainable Cities and Communities – even more critical. SDG 11 states the aim to make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable. While this definition is easy to understand, the concrete measures that need to be taken to achieve this goal are far from clear. 2.1 billion people globally lack safe water at home, poor water & sanitation is still considered the number leading cause of disease and death in the world, and diarrheal diseases kill more children than AIDS, malaria, and measles combined. A clean source of drinking water can make a huge difference to those who have access to one.

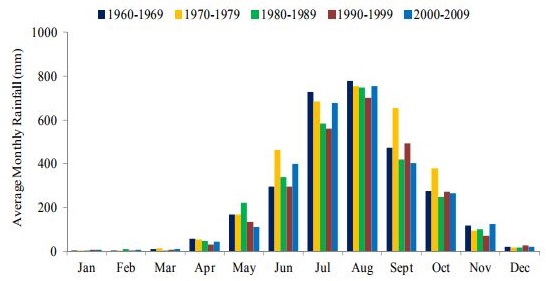

In Sierra Leone’s capital city Freetown, the water supply is in a critical situation. This is not due to a lack of rainfall – Freetown has an average annual rainfall of 2,945mm with the heavy rain during July, August and September being the main months for recharge of surface and subsurface reservoirs – but the water infrastructure of the city.

From: http://uest.ntua.gr/adapttoclimate/proceedings/full_paper/Taylor_et_al.pdf

It relies almost exclusively on a single source, the Guma Dam, which was built in the early 1960s. Between the time of construction and today, the number of dwellers has increased from around 100,000 to 1.06 million people.

Over half the water that enters the system is lost due to leakage from the deteriorated network and informal ‘spaghetti’ plastic pipes. These have grown exponentially over the past 20 years to keep up with the city’s booming population. This has been the only way the Guma Valley Water Company have been able to provide the number of new connections at the rate required. However, these are easily cut deliberately or damaged over time.

Because of the network leakage and the high pressures at which water is supplied to the west coast (the side of the city closest to the dam), by the time water reaches Freetown’s central areas flow and quantity are lower, and then almost non-existent in the densely populated east of the city. This forces much of the population to seek informal sources, such as using the streams that flow through the city. However, these are filled with rubbish and open defecation is very common, which increases health hazards and the risk of disease present in the water.

To improve access to water for the 600,000 people who live in the eastern part of Freetown, I am working on a project run by IMC Worldwide to develop a solution to the city’s poor access to water, which involves rehabilitating and extending the city’s water network by around 80 kilometres.

Balancing competing priorities

As with all cities, there is a battle of space and who gets priority is never an easy call to make. Engineering design of infrastructure needs to consider what is in place and ensure it can continue to perform its designated function.

Within this project, we are trying to fit new pipes within a city that has sprawled in all directions. The Roads Authority insists that all utilities, including water mains, are laid between the drains and buildings walls. However, this space is often too narrow and trying to find best solution that will cause minimal disruption is no easy task.

We need to find a compromise as to where the pipe goes and what impact that will have on either the road or the water supply network. The decision will have to consider the requirement for future maintenance of both infrastructure.

What further complicates the situation is that some of the original pipes throughout Freetown were laid out in the open. However, as the city has grown, they are now surrounded by houses. To access and upgrade them while ensuring that residents in the area are not affected is challenging.

Here is where achieving SDG 11 becomes complex: the need to provide access to infrastructure for the many without negatively impacting a few.

The Freetown Water Rehabilitation project is at the early stages of design, but there is a need to act quickly. Decisions will have to be made, and balances found to ensure that the design of the water supply is inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.