It’s been a good few years since I last visited Venice, but I think it’s an amazing city and as the shower blog is going to have a break in 2019 while I populate the technical side of the website, it was kind of now or never. Plus it gives me a chance to drop in a photo of me when I was still a (relative) youngster! In present-day Venice, water supply is not an issue but where the used shower water goes definitely is. So this is mostly going to be a blog about Venice’s sewer system, by one of the 20 million tourists (who far outnumber the city’s has 271,000 permanent residents) that visit each year.

History of Venice

Made up of 118 separate islands intersected by canals and connected by bridges, Venice was first settled in 400 AD and its heyday as a City state was in the 15th and 16th Centuries. It sits in the Venetian lagoon which covers a total area of 550 km² and is, in large parts, just 1m to 3m deep.

Water supply in Venice

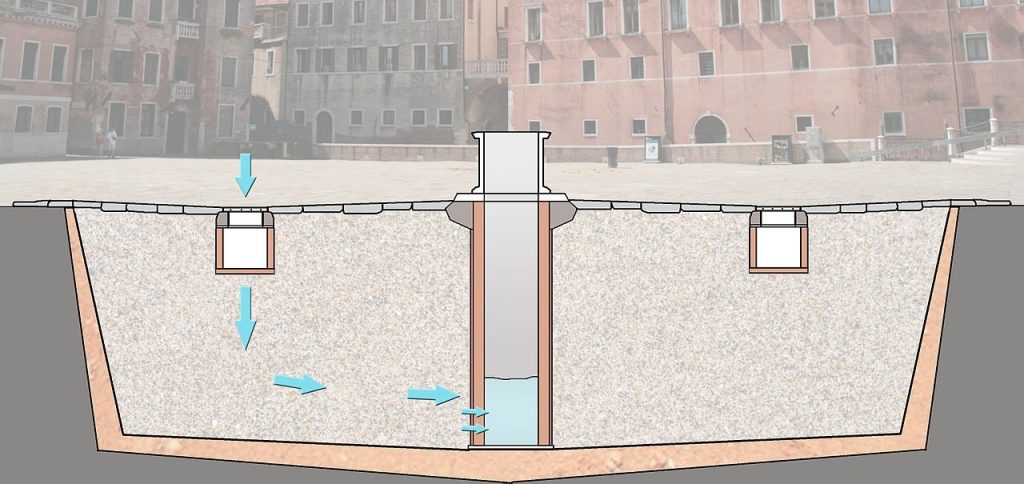

As Venice is in a saltwater lagoon, the usual practice for a city’s water supply (pre a piped mains supply) of digging wells was not possible, so another solution had to be found. This was vere da pozzo (Venetian wells) – sealed water cisterns built to collect, filter and store rainwater. Cisterns of about 5-6 metres deep were dug under the town’s squares (campi). Pavement levels were raised to prevent the salt water from the surrounding lagoon infiltrating the cisterns and the walls and floor were sealed with a layer of local clay. In the centre of the cistern, engineers constructed a tall funnel (canna) made of porous pozzali bricks set upon a slab of Istrian stone – a material that resists salt water well. The canna formed the well shaft and the cistern was filled with layers of clean, wet, river sand and gravel that formed a graduated filter. Rainwater seeped through the loose-fitting paving stones of the campo and collected within the sands of the cistern, where it was filtered before being stored ready for use.

As Venice is in a saltwater lagoon, the usual practice for a city’s water supply (pre a piped mains supply) of digging wells was not possible, so another solution had to be found. This was vere da pozzo (Venetian wells) – sealed water cisterns built to collect, filter and store rainwater. Cisterns of about 5-6 metres deep were dug under the town’s squares (campi). Pavement levels were raised to prevent the salt water from the surrounding lagoon infiltrating the cisterns and the walls and floor were sealed with a layer of local clay. In the centre of the cistern, engineers constructed a tall funnel (canna) made of porous pozzali bricks set upon a slab of Istrian stone – a material that resists salt water well. The canna formed the well shaft and the cistern was filled with layers of clean, wet, river sand and gravel that formed a graduated filter. Rainwater seeped through the loose-fitting paving stones of the campo and collected within the sands of the cistern, where it was filtered before being stored ready for use.

At the height of Venice’s prosperity there were over 6,500 wells and the system was used for over 1,300 years until a supply was finally piped in from the mainland in 1884.

Sewage treatment in Venice

15th-century Venetians dealt with their waste by flinging it out into the streets, as was common then. But, because Venice’s streets were actually seawater canals, the tides conveniently swept the waste out to sea twice a day, keeping the city far cleaner than other medieval cities.

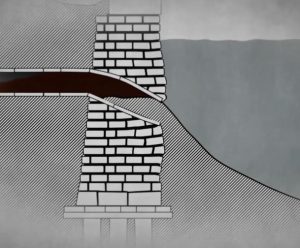

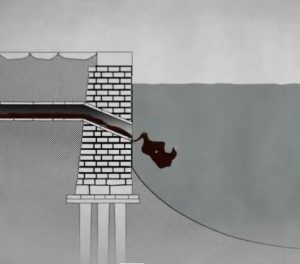

In the 16th Century Venice expanded on this method by developing one of the first sewer systems to be implemented in the world. A series of tunnels, called gatoli, collected and channeled the city’s wastewater into the canals via outlets known as sbocchi; the sewage would then flow out into the waters of the lagoon with the tides.

In the 16th Century Venice expanded on this method by developing one of the first sewer systems to be implemented in the world. A series of tunnels, called gatoli, collected and channeled the city’s wastewater into the canals via outlets known as sbocchi; the sewage would then flow out into the waters of the lagoon with the tides.

As new technology has become available, newer forms of sewage disposal have been implemented. However, these changes have not been made throughout the whole city, and not uniformly to all of Venice’s buildings, so the current sewage disposal system is still a patchwork of old and new. Large parts of Venice are still using this 16th century system, which, while revolutionary back then, is now outdated and inadequate for a modern city.

Sewage Problems

A lack of proper treatment of sewage poses a threat to public health. While private residences and businesses such as hotels are required to have their own septic tanks (which remove solids) many still do not. Significant levels of hepatitis A and enteroviruses have been detected in Venice’s canals. A central sewage treatment plant was built in Porto Marghera in the 1980s, but it is on the mainland, far removed from the main centre of Venice, and whilst some of Venice’s sewage is treated there much of it continues to enter directly into the canals.

Venice’s antiquated sewage disposal system threatens the structural integrity of the foundations and canal walls throughout the city. Without septic tank treatment, the disposal of sewage directly into the canals contributes to sedimentation – the long-term build-up of sediments and solids in the canals.[i] The sediment over time can cause the canals to become so shallow during low tides that they become impassable. Additionally, if the sedimentation blocks the sewage outlets of the buildings adjacent to the canals, the outlets can burst and cause severe damage to the canal wall.

Insula (Venice’s maintenance department) repairs canal walls and sewer outlets that have deteriorated over time.[i] The sbocchi, originally at 1.8 meters below the zero sea level, have been rebuilt higher at 1.3 meters and 0.8 meters to ensure they function correctly and broken gatoli are repaired. But once the sewage is discharged into the canals, the system is still dependent on the tides to carry the sewage from the city out to sea.

Something to think about when you are next showering or using the loo in Venice!

EndNotes

[i] In 1999, a study of the sedimentation in Venice determined that 12 percent of all sediments in the canals come from sewage discharge, a significantly large amount. And sedimentation from sewage is one of the main causes of canal wall damage.

[ii] Insula has also produced this fascinating video, Venice Backstage, which explains a lot of the issues involved in keeping this city functioning, including the problems of its sewers.