The disposal of food waste is a huge problem. Food scraps range from 10% to 20% of household waste and around 40% of total commercial catering waste with approximately 77% of all food waste being liquid. Food waste creates public health, sanitation and environmental problems at each step, beginning with on-site storage (whether internal or external) followed by truck-based collection. Burned in waste-to-energy facilities, the high water-content of food scraps means that the process consumes more energy than it generates; buried in landfill, food scraps decompose and generate methane gas.

And putting food down the drains, via macerators or waste disposal units, along with fat, oil and grease (FOG), contributes to 200,000 sewer blockages and floods across the UK each year. Other disadvantages are rodent infestations, odours and environmental pollution. Macerators are expensive to repair, and use more electricity and water than recycling. Putting food into drains also means an increased organic load at the sewage treatment plant shifting the responsibility for food waste management from the waste industry to the water industry. Modern wastewater plants are effective at processing organic solids into fertiliser products (biosolids), with advanced facilities also capturing methane for energy production, but not all buildings have a modern, upgraded water treatment plant at the end of the sewer pipe. Kitchen waste disposal units increase the load of organic carbon that reaches the water treatment plant, which in turn increases the consumption of oxygen. An Australian study that compared in-sink food processing to composting alternatives via a life cycle assessment found that while the in-sink disposer performed well with respect to climate change, acidification, and energy usage, they contributed to eutrophication and toxicity potentials.

And putting food down the drains, via macerators or waste disposal units, along with fat, oil and grease (FOG), contributes to 200,000 sewer blockages and floods across the UK each year. Other disadvantages are rodent infestations, odours and environmental pollution. Macerators are expensive to repair, and use more electricity and water than recycling. Putting food into drains also means an increased organic load at the sewage treatment plant shifting the responsibility for food waste management from the waste industry to the water industry. Modern wastewater plants are effective at processing organic solids into fertiliser products (biosolids), with advanced facilities also capturing methane for energy production, but not all buildings have a modern, upgraded water treatment plant at the end of the sewer pipe. Kitchen waste disposal units increase the load of organic carbon that reaches the water treatment plant, which in turn increases the consumption of oxygen. An Australian study that compared in-sink food processing to composting alternatives via a life cycle assessment found that while the in-sink disposer performed well with respect to climate change, acidification, and energy usage, they contributed to eutrophication and toxicity potentials.

Waste disposal units in the commercial sector

So, grinding up food waste and washing it down the drain is not an environmentally sustainable solution and food macerators in commercial kitchens have been banned in the UK since 2016.[i] The intention is to ensure that solid food waste doesn’t enter sewers and to increase treatment by anaerobic digestion (AD). This will ensure that the resource value of food waste can be realized and that food waste is managed in compliance with Article 4 of the revised Waste Framework Directive.

Waste disposal units in the domestic sector.

The food macerator was invented in 1927 by John W. Hammes, and first appeared on the US market in 1940. In the United States, 50% of homes have waste disposal units compared to just 6% in the UK. They were originally banned in New York City but that ban was rescinded in 1997 following research that showed the overall effect on the city would be less, especially due to the reduction of foxes, rats, flies and cockroaches attracted by piles of food waste.

In 2003, a life-cycle analysis comparing various food waste collection systems, conducted by the University of Wisconsin, concluded that macerators do offer advantages over the dustcart in terms of reduced greenhouse gas emissions, road traffic and lower overall costs to local authorities, though water use was higher (as much as 16 litres per use). [ii] The ‘lower overall costs to local authorities’ findings led (in 2006) to Herefordshire Council and Worcestershire County Council offering rebates of up to £80 to residents installing a food macerator in their kitchen though this incentive has now ceased.

Other solutions

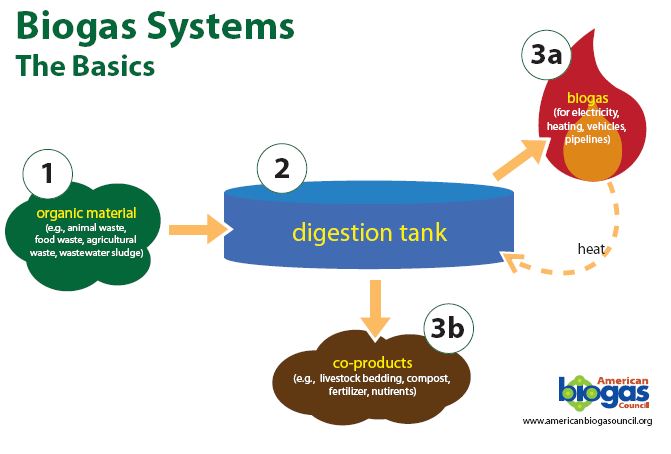

Food collection for composting and anaerobic digestion are considered the best options in the UK. They both require food to be separated in the waste stream. Bio digesters are fed with organic material, which is broken down by micro-organisms in an oxygen-free environment to produce methane (often called biogas and used as a substitute or replacement for natural gas) and a digestate that is mainly used as fertiliser. This short video shows the process works at Michigan State University. There are currently 640 recorded active anaerobic digestion plants in the UK.

[i] Scotland (2016), Northern Ireland (2017), England and Wales (2018).

[ii] Another study, based on a LAX Airport proposal to divert 8,000 tons/year of bulk food waste into the wastewater stream, showed that food waste produces three times the biogas when compared to municipal sewage sludge. The value of the biogas produced from anaerobic digestion of food waste appears to exceed the cost of processing the food waste and disposing of the residual biosolids.